Topic 9: Makerspaces

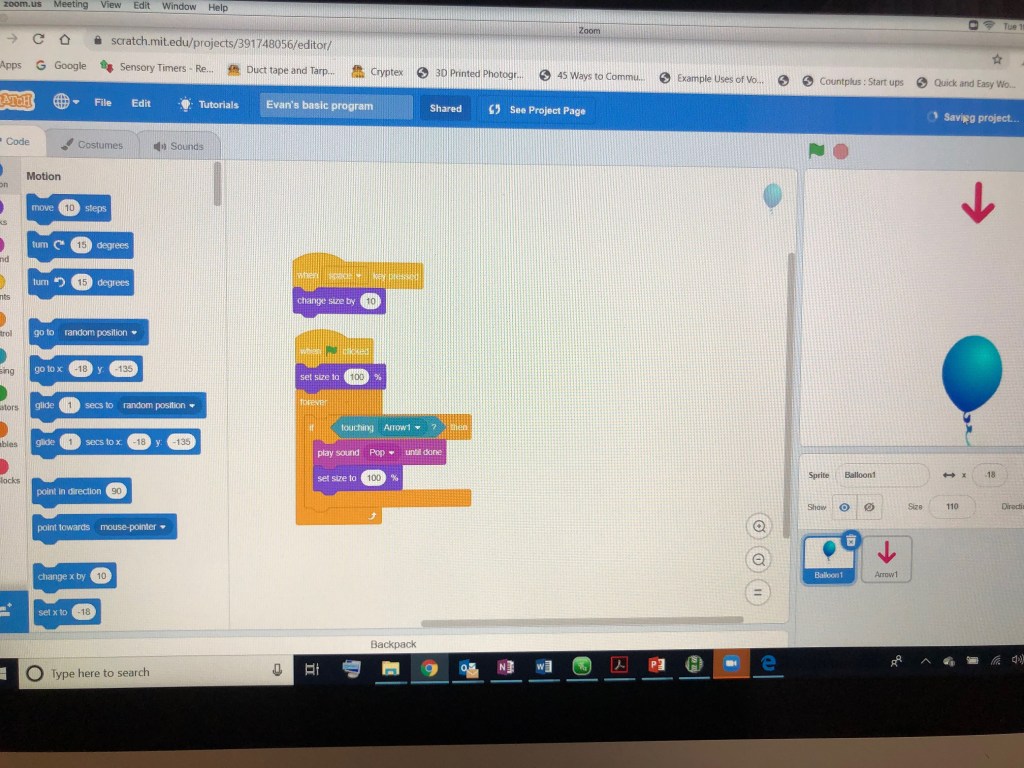

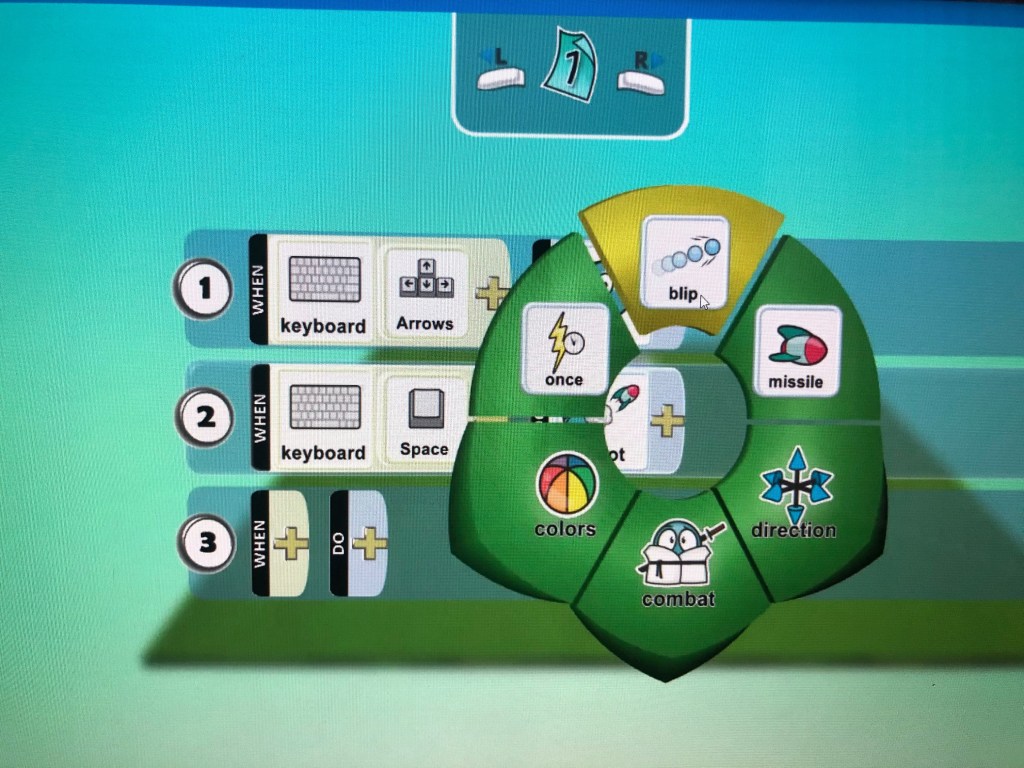

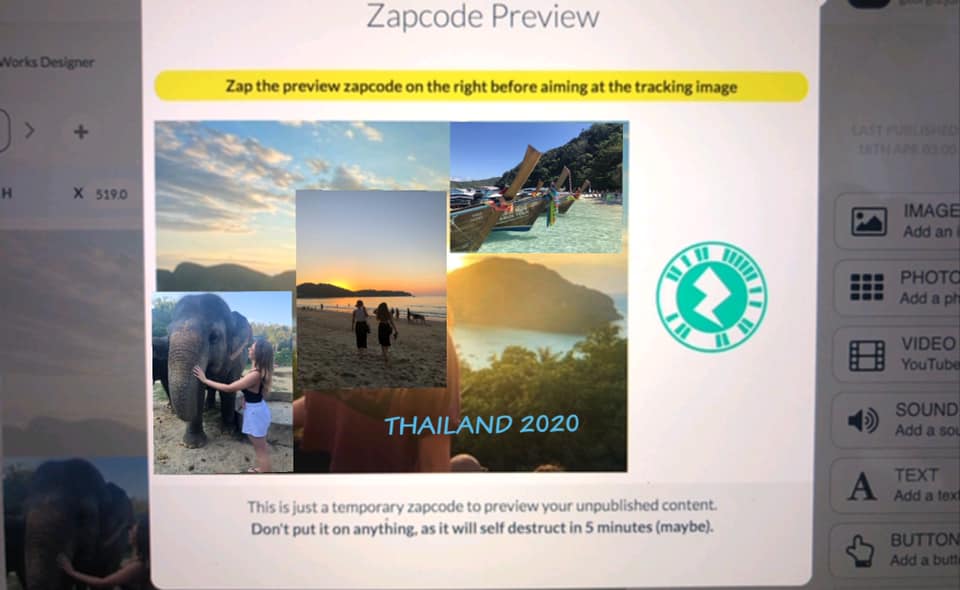

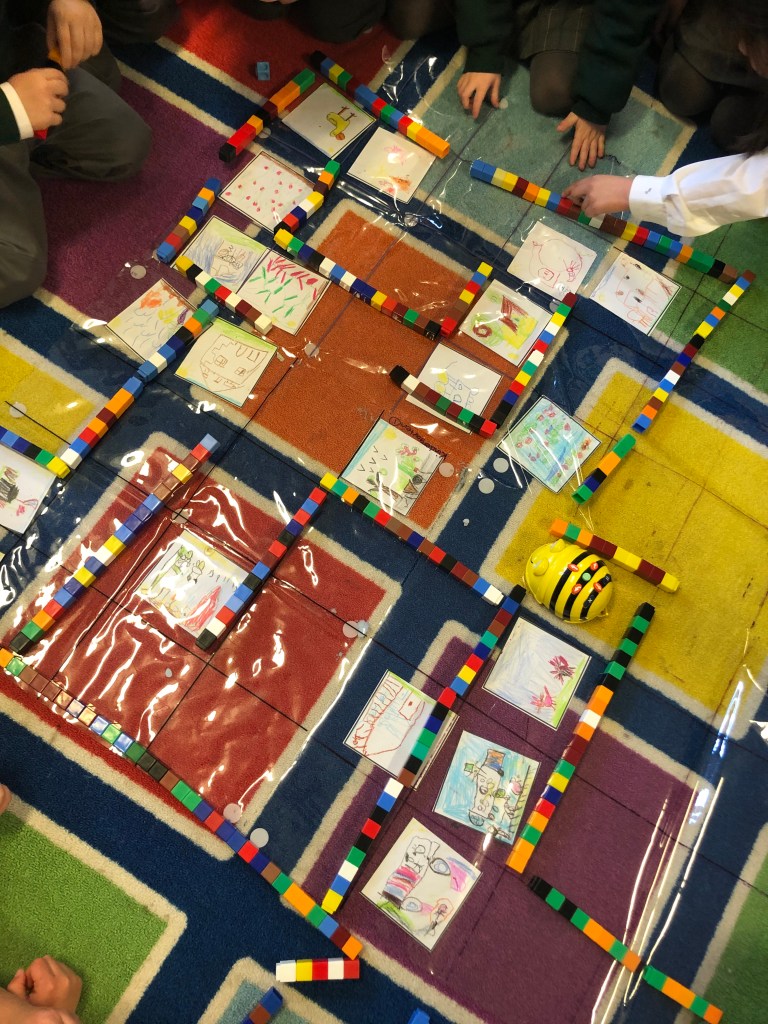

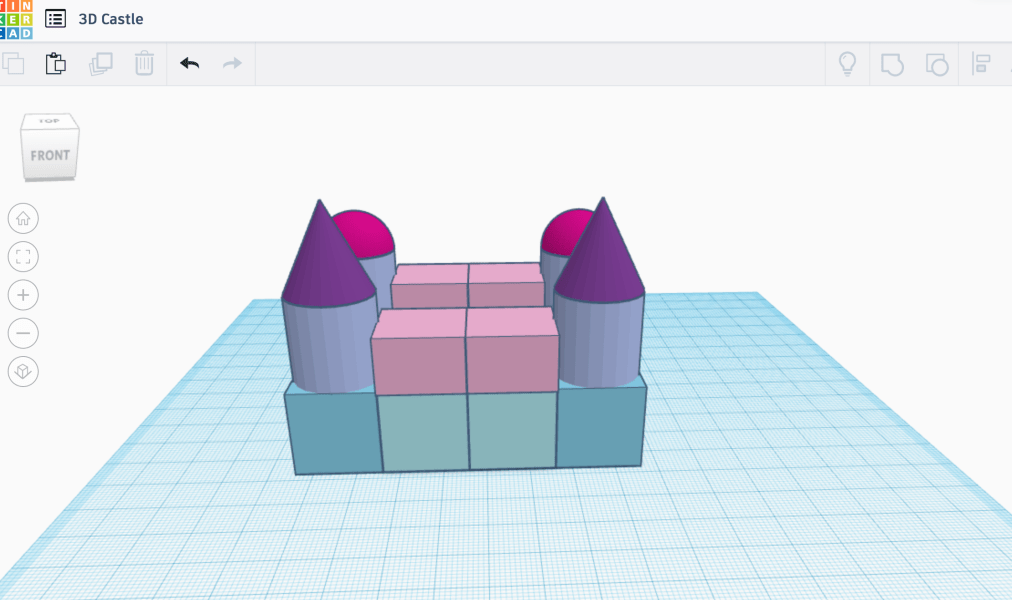

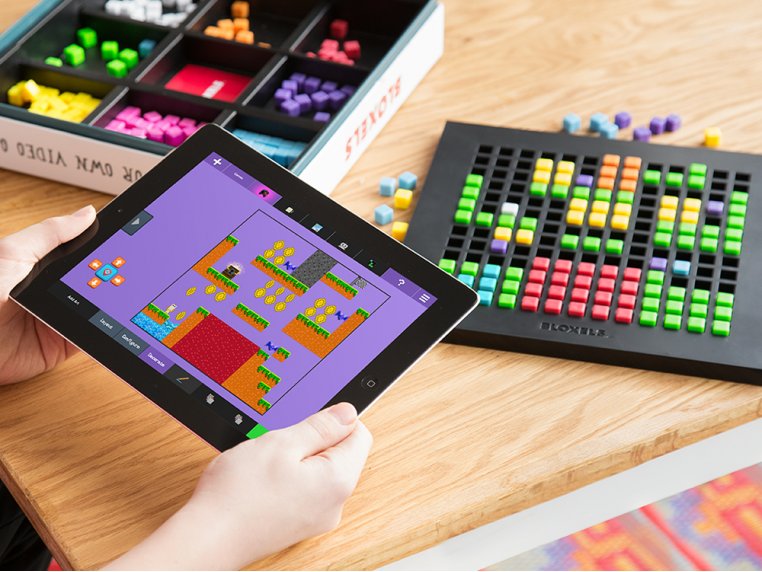

A Makerspace in education, is a zone or a workshop where students are given digital tools and resources to tinker with, in order to support the invention of something new (Welbourn, 2019). Students are given the opportunity to problem solve whilst collaborating with others within a shared space. The digital technologies used within these spaces give students the opportunity to explore multiple STEAM learning areas and facilitates the constructionism theory of learning (Welbourn, 2019). A Makerspace is a hotbed for creativity as students are given the freedom to explore multiple digital tools in a self inquiry based learning environment (Welbourn, 2019).

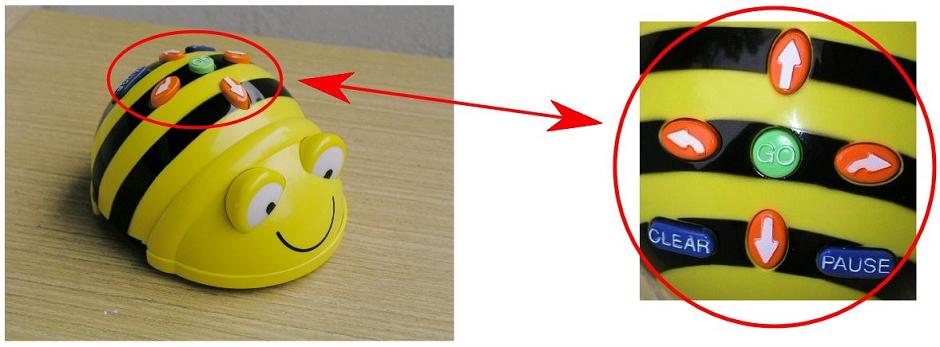

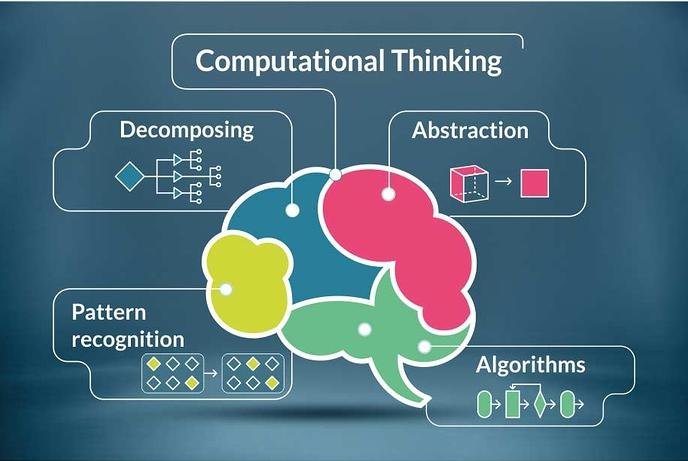

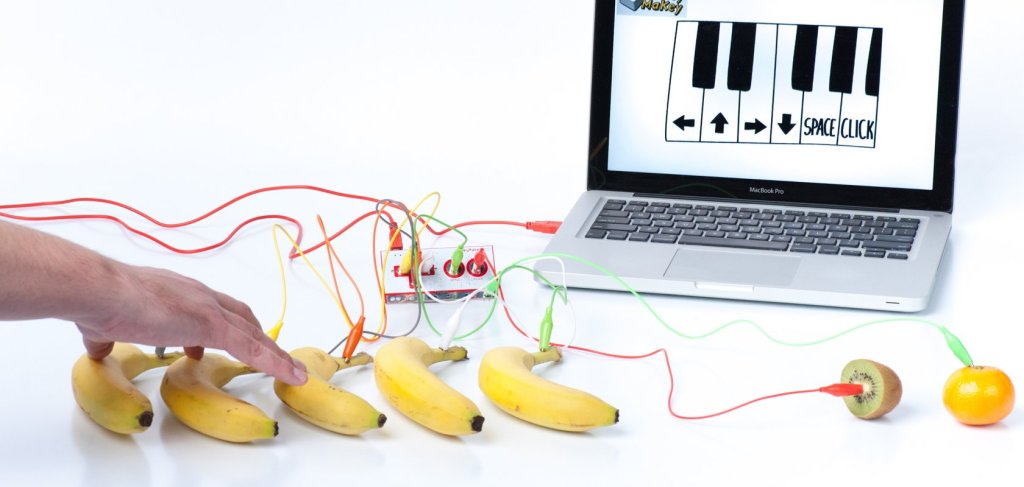

Makey-Makey is an example of a digital tool that can be utilised within a Makerspace. Makey-Makey is an electrical circuit kit that allows students to explore the concept of conduction and electricity in a non-traditional way (Fokides & Papoutsi, 2020). Students use everyday objects as conductors in order to make a closed circuit that connects to a computer (Fokides & Papoutsi, 2020). This diverse digital tool allows students to explore aspects of science and technology as well as coding concepts (Fokides & Papoutsi, 2020). This emerging technology gives students a different perspective on electricity, further demonstrating how technology can enhance learning and foster creativity. Chibi lights is another example of a digital technology that utilises electrical circuits for learning. Using LED lights and sensor stickers that glow when there is a flow of electricity allows students to see their learning in action (Welbourn, 2019). Finally, another example of a Makerspace technology is BBC Microbit. BBC Microbit facilitates the learning of computer literacy as well as computational thinking and coding (Schmidt, 2016). With computational thinking becoming a widely recognised 21st century skill, Microbit is growing in popularity amongst teaching classrooms (Schmidt, 2016). Designing a make-code that projects a design onto the Microbit coding board is the first step for students in developing computer literacy.

All of these technologies are examples of digital tools that can be used in a Makerspace. Moreover, implementing these digital tools within classrooms is made easier with the Maker Project Rubric. The rubric allows both teachers and students to recognise the steps needed in order to make a project exemplary. Furthermore, creativity is at the centre of a Makerspace as it facilitates the construction of unique ideas, developed from everyday concepts.

References:

Fokides, E. & Papoutsi, A. (2020). Using Makey-Makey for teaching electricity to primary school students. A pilot study, Education and Information Technologies, 25, 1193-215.

Schmidt, A. (2016) Increasing Computer Literacy with the BBC micro:bit, IEEE Pervasive Computing, 15(2), 5-7.

Welbourn, S. (2019). The Making of a Makerspace: A Handbook on Getting Started, Faculty of Education, Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario, 1-144.